There was no way I could have known the implications of what I did. I simply saw it as news — breaking news. So, the first instinct was to have it published and think about the possible effects later — if any. That’s the way we were trained — publish and damn the consequences as long as the story is factual with no legal or national security risks. I did just that. Maybe I was wrong.

Yes, I was a corps member — just like dozens of others in the camp with me. But as that famous writer has observed, all animals may be born equal but some are more equal than others.

While other corps members were fresh from school, I was on a leave of absence — from Pioneer newspaper, where I was already working. It may interest you to know how much I was earning as a reporter then. That is a story for another day.

The event of that day made far more meaning to me than others. First, I was already a practicing journalist — with a little over 10 years in the newsroom. I got involved in journalism on July 29, 1985, when I was sent on internship at the then Nigerian Chronicle. That was where and when I met Nnamnso Umoren, who was then the acting news editor; Uko Okopido, the chief sub-editor; late Etim Anim, who was Sunday Editor/Editor-in-Chief; and late Patrick Okon, who was the Daily Editor. I can’t forget John Ebri, Parchi Umoh, Joshua Okpo and Unimke Nawa — all of blessed memory.

I was then a student at the good old Calabar Polytechnic. By the time I completed my Ordinary National Diploma the following year, I was already a regular contributor to the paper. By that time, I had gone through the newsroom headed by Nawa; proofreading, headed by Okon Osung; and sports — under the grandmaster, Paul Bassey. Some people thought I was a staff. I wasn’t. Those were the days when it was more like a status symbol to have a lead story on the front page of a national newspaper.

Let’s fast-forward to November 10, 1995. The degree of cold that morning was pretty unusual. It was harmattan period. Added to this was the fact that we had just been ushered into a community called Efon Alaye in the present Ekiti State, to begin our national service. Efon Alaye is a rocky community surrounded by some thick forests and hills. When it is cold, it is bone-cracking cold. You simply walk around like animated ice-block. But when the heat walks in, it is as though someone forgot to close the doors and windows of hell after dumping one sinner inside.

Forced out of bed to the parade ground, I had no time to tune my transistor radio for the news. I simply brushed my mouth and jumped into the required attire for the parade. Fortunately, based on my training and passion, I was drafted to the Camp Radio—you know what I mean. What constituted the Camp Radio were half a dozen or more deafening loud speakers connected to every part of the camp so that no matter where you were, you must hear every announcement and music put out by those authorized to do.

News on Camp Radio comprised announcements from the camp commandant or the State Director of the National Youth Service Corps. I was expected to edit whatever others brought in as news before they were put on air. Once in a while, we picked real news from local radio stations or old newspapers and broadcast them to the corps members. I refused to go near the microphone—of course you know that I have a great voice!

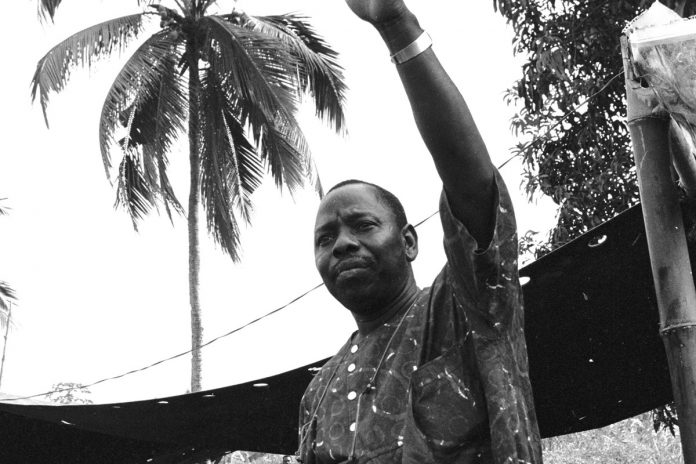

Towards the evening of that day, when all activities had almost ended, I grabbed my small transistor radio, which was permanently tuned to either VOA—Voice of America—or BBC—British Broadcasting Corporation. It was on the VOA that I heard the news. Unbelievable! I can’t remember exactly the wordings of the news. But the summary was that Ken Saro-Wiwa and some others who were standing trial for alleged murder of certain Ogoni chiefs, had been executed by hanging. What! Ken Saro-Wiwa killed—strangled to death? Then the newscaster mentioned that Ledum Mitee, a lawyer, and a few others were spared. The tribunal did not actually condemn them.

I jumped off my bed and headed towards the Camp Radio Station. One little privilege we enjoyed as “staff” of the radio station was that while others observed compulsory siesta or were on the parade ground, we were allowed to move about because we were on essential duty.

Inside the studio, I sat down and put the story together—just the way VOA did—accusing the Sani Abacha government of insensitivity and bloodthirstiness. With the little freedom accorded us, the story did not need to go through any superior officer before it was put on air. I even added my own small salt and pepper based on my little knowledge of the case.

Gbam! The story went on air. It was breaking news—although it must have happened anytime between morning and that evening. After about an hour, I quietly left the studio and headed in the direction of my hall with the instruction that the news be aired at the end of every announcement submitted by the Camp Commandant. I was hardly back in bed when my name came on air. I was directed to report to the Camp Commandant immediately. Ignorantly, I jumped off the bed thinking there was an announcement to write, edit and air.

As I walked towards the studio, I noticed that Sam—the public relations officer of the State NYSC— was there with more than half a dozen soldiers attached to the camp. Suddenly, a 504 wagon conveying the State NYSC Director pulled up. She stepped out a bit faster than usual. The Camp Commandant, Captain Fakrogha, unsmiling, walked towards her. Instantly, I knew something was wrong. While they talked, I stood a few meters away, surrounded by soldiers. It was Sam, who, a few minutes later, told me what had gone wrong. My breaking news had broken all the camp rules.

The options before camp was to either have me arrested as suggested by the commandant, and taken away from the camp; or remove me from the radio station, with additional extended stay at the end of the service year; or cause me to frog-jump around the camp as many times as would make them happy. He was seeking the approval of the director on any of the options. None was approved because any of them could attract reactions from the other corps members.

At the end, I wasn’t harassed. I was only asked a few questions in a stern voice, regarding the source of the news and the fact that the station was not set up for that purpose. The news was immediately yanked off the air and the station shut down for an hour or two. From that moment onward, every news story that was not based on internal announcement, camp sports, among others, were to be approved by Sam.

That was my experience on the day Saro-Wiwa was killed by Abacha and his gang. It was a bad day for Nigeria. Reactions across the world made every Nigerian feel like bad news. On the camp, soldiers took positions in anticipation of reactions from corps members.

Fortunately, there was none. In fact, corps members were confined to their beds that evening—just in case. Not many people even knew about the incident. To them, the news was of no consequence. Under Abacha’s government, violent death was almost normal. Just as Dele Giwa once wrote, Nigerians had been shocked to a state of unshockability. Perhaps, the death of Saro-Wiwa and others was just one of such deaths.

Akpe is an Abuja-based journalist.