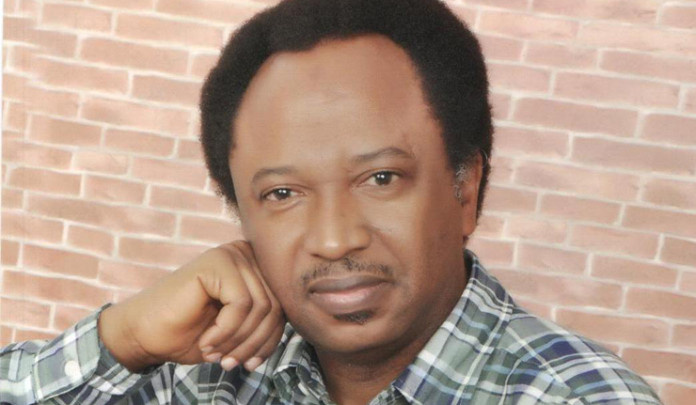

As the senator representing Kaduna Central, Shehu Sani, failed to get the re-nomination ticket of the All Progressives Congress last week, not a few looked for blood in the hands of Governor Nasir El-Rufai. His pitchfork is never far from him.

When El-Rufai fights, he doesn’t use his size or pick an enemy in his weight class. His quest is sometimes driven by emotional scars from bullies back in his secondary school days. He fights with concentrated brainpower and energy, punching well above his physical weight and hardly leaving the enemy without something to remember.

This same President Muhammadu Buhari whom he now adores with the charming courtesies of a schoolboy was once his victim. They were on opposite sides of the political divide at the time, when core Buhari loyalists used to accuse El-Rufai of being the brainbox of the rigging machine of the People’s Democratic Party.

One of the most memorable things that El-Rufai said when Buhari was still trying to shed his rustic, rural image, was that the then presidential candidate of the Congress for Progressives Change did not know the difference between the blackberry fruit and the Blackberry phone. He seemed to suggest that even if a GPS was pre-configured to lead Buhari to the Presidential Villa, the man would, somehow, still end up in his cattle ranch in Daura.

One million crooked courtesies cannot erase that.

El-Rufai has also given as much as he has taken from three former presidents – Olusegun Obasanjo, late Umaru Yar’Adua, and Goodluck Jonathan, with his encounter with Obasanjo ranking as another extraordinary episode in his accidental public service career.

A man equally gifted for making enemies and friends without fear or favour, El-Rufai has left his mark on people as he has on the places he has passed through, as well.

Apart from late General Mamman Vatsa, no one has changed the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, as remarkably as El-Rufai. In spite of threats to his personal safety and resistance by the high and mighty in a hurry to make Abuja a slum, El-Rufai fought a determined battle to take the city back and he did a good job of it.

When he became governor of Kaduna State nearly four years ago, he appeared determined to repeat in the state what he had done in Abuja. But in making the Kaduna omelette, his party man and senator, Shehu Sani, would, among others, turn out to be one broken egg too many.

It all goes back to the beginning – that is, the spoils-sharing time after the 2015 elections. It was not only a Kaduna problem; it was an APC problem. The party seemed to have spent so much time plotting to dislodge the PDP government that, when it finally won, it didn’t know what to do with power.

Until recently, hundreds of Federal ministries and parastatals were still firmly under the control of PDP agents, forcing First Lady Aisha Buhari to warn that there would be a rebellion if the situation did not change.

Sani’s list of political appointees to El-Rufai for nomination into the new Kaduna cabinet met a brick wall, giving the impression that nothing had been discussed or agreed earlier. El-Rufai put the list in the shredder and chose his own team without saying a word to Sani. That was the first cut. It’s been downhill from then.

In the last three and a half years, Sani has mounted a one-man opposition against El-Rufai’s government – and even the Federal Government – more vigorous and, sometimes, more brutally efficient than the opposition PDP.

On the issues of the governor’s attempt to rid Kaduna streets of beggars, the clearing of “illegal structures”, the sacking of incompetent teachers, the management of the multiple religious crises in the state, the fight against corruption and $350 millon World Bank loan, the governor and the senator have been at dagger’s drawn.

Sani was right on the well-intended but poorly handled Kaduna demolition as indeed he was about Buhari’s dithering which has made the President captive of corrupt insiders fighting corruption.

But Sani was wrong to insist that El-Rufai must retain incompetent teachers whom he would not employ to teach his own children and also wrong to block the World Bank loan, not for lack of merit, but mainly because he wanted to teach the governor a political lesson. That last one was a mortal sin.

What I don’t understand is why after an extended suspension and the many wars with the state chapter of the party, which is in the governor’s pocket as indeed most state party chapters, Sani still hoped he would get the party’s ticket by the self-imposed errand of milking Buhari’s cow. How?

Buhari wouldn’t be Buhari if he has not mastered the art of looking without seeing and reigning without being in charge.

If Sani had asked Suleiman Hunkuyi, the other former APC senator on his side on the war against El-Rufai, he would have told him that the governor takes no prisoners. Hunkuyi was El-Rufai’s DG during his governorship campaign, but the two soon fell out over control of the party’s structures and things have never been the same.

Rather than fool around for a soft pass from Aso Rock, Hunkuyi took his fate in his own hands and defected to the opposition PDP where he contested for the governorship ticket – and lost gallantly.

How Sani, a democrat, hoped to get the APC re-nomination ticket on his own terms and without a contest beats me. It remains to be seen if embattled party Chairman Adams Oshiomhole who backed his ambition would also press for direct primaries in Edo State when the time comes. But surely direct primaries do not mean backdoor presidential anointing. A slug is a slug.

Whatever the case, Sani is down, but certainly not out. As top lawyer Jiti Ogunye said in his recent article on the APC primaries in Lagos, that primaries are the internal affairs of the parties. They are not substitute for general elections and never will be.

If INEC’s window has not closed, it would be interesting to see how Sani’s new party, the People’s Redemption Party, performs against his main rival and El-Rufai’s protegee, Uba Sani, in next year’s senatorial election for Kaduna Central. Voters will, ultimately, decide.

Sani’s generous resignation letter carries the echo of a man who is leaving to fight another day, hardly the hint of bitterness of a wounded soldier. His revenge would be to defeat El-Rufai’s man at the poll, or else prepare for the irreversible journey to political oblivion.

Only he can remove the dagger in his back; that is, if he moves fast enough before one final twist leaves him mortally wounded.

– Ishiekwene is the managing director/editor-in-chief of The Interview and member of the board of the Global Editors Network